Image courtesy of Fiona McMurrey

Image courtesy of Fiona McMurrey

Love, in France, has never been a simple promise of happiness. Long before cinema, before cafés became symbols of romance, French literature was already teaching readers that love is complex, restrained, and often unresolved. Through novels, letters, and quiet confessions on the page, France learned to see love not as fantasy, but as an inner experience — shaped by time, memory, and moral tension. To understand French attitudes toward love today, one must begin with the books.

Love as an Inner Life

One of the most influential love stories in French literature, La Princesse de Clèves by Madame de Lafayette, set the tone centuries ago. Published in the 17th century, it shocked readers not with scandal, but with restraint. Love existed largely through silence, hesitation, and ethical conflict. The most important moments happened internally. This novel established a lasting French idea: love is not defined by what we do, but by what we feel, resist, and reflect upon. Passion alone was not enough. Love was something that tested character. That idea never disappeared.

Passion, Illusion, and Disillusionment

As French literature moved into the 18th and 19th centuries, writers became increasingly suspicious of unchecked passion. In Manon Lescaut by Abbé Prévost, love is intoxicating but destructive. Desire leads not to fulfillment, but to ruin. The novel does not condemn love — it questions it. Later, Gustave Flaubert would deliver one of the most devastating critiques of romantic illusion in Madame Bovary. Emma Bovary’s tragedy is not that she loves too deeply, but that she loves what literature promised her instead of what life offered. In France, this novel became a cultural warning: love imagined can be more dangerous than love lived. French literature did not reject romance. It insisted on honesty.

Love as Self-Discovery

Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir pushed this realism further. Love in the novel reveals ambition, insecurity, and self-deception. Relationships are mirrors rather than escapes. Falling in love means discovering uncomfortable truths about oneself. This approach deeply influenced French emotional culture. Love was no longer just about union; it was about self-knowledge. To love was to confront who you are. That theme continues well into modern French storytelling.

Memory, Jealousy, and Time

No French writer explored love’s inner complexity more thoroughly than Marcel Proust. In À la recherche du temps perdu, love is inseparable from memory and jealousy. It is lived, remembered, reimagined, and suffered long after it ends. For Proust, love is never stable. It exists in time, constantly reshaped by absence and recollection. This vision of love — obsessive, reflective, and deeply psychological — profoundly shaped how France understands emotional attachment. Love, in French literature, is not an event. It is a process.

Quiet Desire and Emotional Restraint

In the 20th century, writers like Colette and Françoise Sagan refined the art of emotional subtlety. Colette’s La Vagabonde presents love as a question of independence. Desire exists, but so does the need to remain oneself. Choosing solitude can be as meaningful as choosing romance. Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse captures youthful love with cool restraint. Emotions are powerful, but never exaggerated. What makes the novel enduring is its refusal to moralize. Love simply unfolds — and leaves consequences behind. This restraint feels distinctly French: feelings are acknowledged, but never overstated.

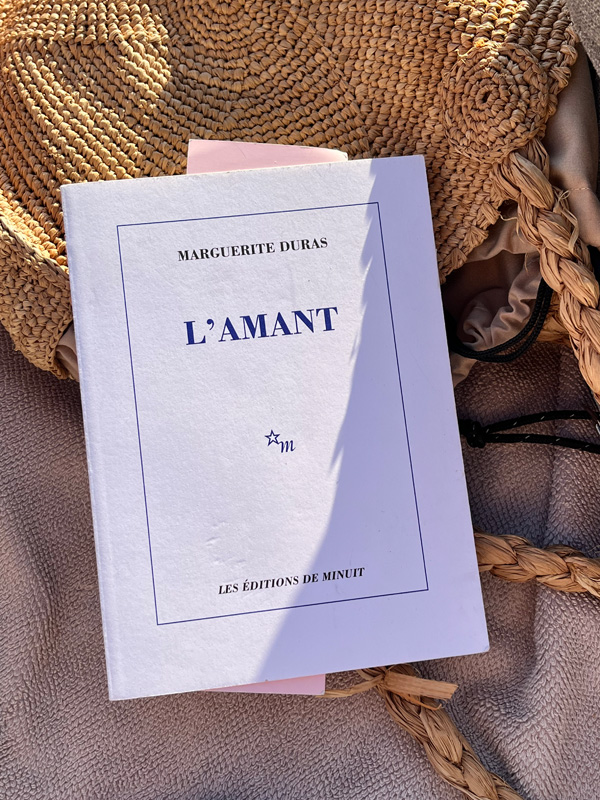

Love Through Silence and Absence

Few writers embodied French literary intimacy as completely as Marguerite Duras. In novels like Moderato Cantabile and L’Amant, love is fragmented, often unsaid. Conversations circle around what cannot be expressed. Silence becomes as meaningful as dialogue. Duras’s work reflects a broader French literary truth: absence is often more powerful than presence. Love does not need resolution to be real. This sensibility echoes through French cinema today, where pauses, glances, and unfinished sentences carry emotional weight.

Letters, Distance, and Longing

French literature also gave love a written form. The Lettres portugaises, one of the most famous collections of love letters in French, elevated longing into literature. Love expressed through writing — delayed, unanswered, incomplete — became a national emotional language. Even when love is distant or unreturned, it remains meaningful. Writing preserves feeling when presence cannot. This tradition helps explain France’s enduring affection for letters, notebooks, and handwritten expression.

Why French Love Stories Rarely Promise Happiness

Across centuries, French novels have returned to the same conclusion: love matters not because it makes us happy, but because it reveals us. It teaches patience, humility, self-awareness, and loss. French literature does not offer easy endings. It offers understanding. This literary inheritance still shapes how love is portrayed in French films, how relationships unfold, and how intimacy is valued in everyday life. Romance is not something to conquer or display. It is something to inhabit carefully.

Love, Written Slowly

From Madame de Lafayette to Marguerite Duras, French literature has taught generations to approach love with attention rather than urgency. To listen before declaring. To feel before acting. To accept that love may transform us without ever resolving neatly. This is why love in France often feels quieter, slower, and more reflective. It was written that way first.